Bob Speake, One of Bilko's Boys, Dead at 94

Bob Speake was sitting in the office at his home in Topeka, Kansas, when he pointed out a picture on the wall.

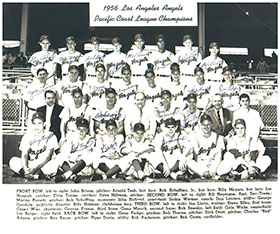

"This group of guys knew what they were there to do," Speake said of the 1956 Los Angeles Angels team photo. "They weren't going anywhere in the immediate future. The Cubs weren't having a year in '56 any better than we did in '55, nor any better than we did in '57."

He paused to reflect before adding a final thought about the team. "We were like a family. There was such a tight camaraderie around Bilko. We became Bilko's Boys."

Speake died in his sleep October 3, 2024, in Topeka at the age of 94. He is survived by his wife of 74 years, Joan Speake; brother Jack Speake; sons Dr. Bruce Speake, Bob Speake and Jim Speake; eight grandchildren and nine great grandchildren.

Playing left field for the Pacific Coast League champion Angels in '56, Bob batted .300 with 25 homers and 111 runs batted in while tying for the league lead in most double plays by an outfielder - six.

As impressive as these numbers were, they paled compared to teammate Steve Bilko's league-leading .360 average, 55 round-trippers and 164 RBIs. The Angels posted a 107-61 won-loss record, finishing a whopping 16 games ahead of second-place Seattle.

"Bilko was the shining star - the 'pede' on the pedestal," Bob said of the team that became known as The Bilko Athletic Club. "He brought us all along and caused each of us to have a good year. We were all confident - especially me."

The Chicago Cubs sent Speake to L.A. to recover from a wrist injury he suffered in St. Louis at the end of the '55 season. He crashed into the left-field wall at Sportsman's Park while making a game-saving catch.

The bases were loaded with two outs in the bottom of the 11th when the Cardinals' Alex Grammas hit a ball to deep left-center field. As Speake raced toward the concrete wall in left field, he could hear Centerfielder Gale Wade running behind him and hollering: "Plenty of room! Plenty of room!"

"You keep saying plenty of room as long as the guy can catch the ball and not get killed," Gale explained. "If you can catch the ball and only hit the wall, so what? I kept telling him, 'Plenty of room!' He went back and caught it and then he hit the fence."

"I went sideways into it," Bob added. "And in trying to protect myself, I got my hand trapped between my body and the concrete wall. It was just a split second. It was the wrong place to have your hand."

Speake was carried off the field on a stretcher with a severely dislocated left wrist. "I could scratch my elbow."

Over the years, the play became the subject of good-natured bantering between the two Missourians and long-time friends.

"He always said that I ran him into the wall," Gale said. "Heck, just a broken wrist for one out, that ain't bad!"

"I had teeth marks on that wall," Bob joked.

"Oh, he made a great catch - a heckuva catch," Gale gushed.

"There's only one problem," Bob said. "He dislocated his wrist!"

"I know and I wasn't concerned about that," Gale deadpanned. "That's secondary."

Bob turned serious: "That's how I wound up in Los Angeles."

Ironically, Speake was responsible for Bilko winding up in L.A. in '55.

Speake reported to the Cubs spring training camp as a first baseman, the only position he had played in five years as a professional. He was a rookie trying to make the big jump from Class A to the majors, so he was given little chance of displacing Bilko as the backup to Dee Fondy, the starter.

"I had a hot spring in '55," Speake said. "And Bilko had sort of bounced from pillar to post. So, the tossup was either me or Bilko. They kept me."

Bob was used as a pinch-hitter initially, delivering four hits and a walk in nine at bats.

On arriving in Philadelphia May 1 to play the Phillies in a doubleheader, Cubs Coach Bob Scheffing asked Speake if he had ever played the outfield.

"Yes, I played one game in the Army," he replied.

"Get a finger mitt and go out there and get some fungoes," Scheffing said.

Bob borrowed a glove from a Cubs pitcher and chased fly balls in the outfield. "I must've looked like an idiot with those wind currents from the double-deck."

The next morning, he went to a Philadelphia library and read a book by Terry Moore, an outstanding defensive centerfielder for the Cardinals in the 1930s and 1940s. "It's the only place I knew to find out how to play the outfield," Speake said. "He talks about the convex and concave walls, getting in front of the ball and hitting the cutoff - things that you learn in spring training. That's the only outfield education I had. I was in the lineup that night."

Speake replaced slumping Hank Sauer in left field. He went hitless in three at bats but turned in a defensive gem by doubling up a runner at first base after catching a fly ball.

The next game, Speake sparked another Cub victory with a bases-loaded triple. In his third start, Speake hit a home run against the New York Giants that soared over the Polo Grounds' two-story roof in right field.

The home run was the first of 10 Speake smacked in May. By the end of the month he was Captain Mayhem with Cub fans chanting "Speake to me" each time he came to bat. "Speake up" was the watchword at Wrigley Field - "things will be all right with the Cubs whether they're behind or not."

With Sauer riding the bench, packs of Beech-Nut chewing tobacco that bleacher fans previously showered on the popular "Mayor of Wrigley Field," now peppered Speake after he hit a home run. "He was MVP," Speake said of Sauer, the National League's Most Valuable Player in 1952 and coming off his most productive home run year (41) the season before. "I'd come into the dugout, and I'd have tobacco pouches, and I'd dump them in Sauer's lap. He'd say, 'Boy, now take one.' I said, 'I don't want 'em.'"

Born August 22, 1930, in Springfield, Missouri, Speake was dubbed "Wonder Boy of the Ozarks."

"Every time we needed a timely hit he came through and he was socking homers as if he were another Babe Ruth," raved Wid Matthews, personnel director of the Cubs.

On May 25, Speake hit a line-drive homer onto the right field catwalk at Wrigley Field to beat the Cardinals. He hit home runs in each of the next two games.

In the Cubs' doubleheader sweep of the Cardinals on May 30, Speake homered in both games, inspiring a Chicago Tribune story titled: CUBS SPEAK(E) WOE FOR CARDS. The Chicago Sun-Times featured a box score headline reading: BOB-BOB-BOBBIN' ALONG.

"I never saw anybody have a greater single month than Speake did," said Cubs Manager Stan Hack. "Whenever we needed a run to win he came through for us."

The year before - 1954 - the 6-foot-1, 180-pound Speake hit .264 with 20 home runs and 82 RBIs at Des Moines in the Class A Western League.

"How does he do it his first year in the majors?" a sportswriter asked Rogers Hornsby, the Cubs batting instructor and one of the greatest hitters of all time.

"It's easier to hit major league pitching if you've got any guts," Hornsby said. "Speake's got it, too. You can tell by the way he stands up at the plate. No one who was ever scared of a pitcher was ever a good hitter."

On June 3 against the Giants, Speake homered again - his 11th of the season and eighth in 14 games.

On June 7 the Tribune's Edward Prell wrote: "The best left fielder in the league as time for the July 12 All-Star spectacle in Milwaukee nears is 24-year-old Bob Speake of the Cubs. Not even his most rabid followers will class the Missouri Ozarkian with either Mays or Musial. But this All-Star game should reward current great play."

Speake began June hitting .304; he ended the month with a .252 average - only seven hits in 47 at bats. By mid-June, he was on the bench and Sauer back in left field.

The Cubs started June in second place, six games behind the league-leading Brooklyn Dodgers. Over the next two months they had a 23-39 record. At one point, they lost nine straight games and 15 of 16. They finished sixth, 26 games behind the first-place Dodgers.

The scuttlebutt around the National League was "wait 'til the second swing." In other words, the Cubs start fast but second time around, they go into the tank. "And, boy, we did," Speake conceded. "We were in second place and then suddenly, it didn't matter whether you won or lost. If you won, great! But you were expecting to lose."

Speake finished with 12 homers, 43 RBIs and a .218 batting average. Sauer didn't do any better: 12 four-baggers, 28 RBIs and a .211 average.

Speake wasn't happy about going back to the minors in '56, but he was looking forward to playing every day for the Angels managed by Scheffing. Just as he did with the Cubs the previous May, he went on a home run rampage, rapping eight. Meanwhile, Bilko belted 16.

"The electricity off of Bilko caught us all," Speake said. "We became his greatest rooting section. When he hit one, we all became electrified and wanted to do as well as we could. We wanted to be part of his domain."

Part of Bilko's domain was the whirlpool in the Angels clubhouse. "Bilko and Freese (George Freese) always had a six-pack after every game. So. I sat down, opened a beer and took a couple of swallows. I never liked the stuff and reaffirmed at that point that I didn't."

The magic potion for Speake was winning.

"Ball players of that era, as a rule, never got close to each other," Speake recalled. "There was a saying: One-a-comin', one-a-playin' and one-a-goin' because we were chattel mortgage. We were under the reserve clause. It was dangerous to become close."

Chuck Connors, the baseball player-turned-actor, often barged into the Angels clubhouse after a home game shouting, "Sweat, sweat, you slaves, sweat!" and asking: "Which one of you is not going to be here next week?"

"Here comes Dog Food Man!" the players yelled back, referring to the dog food commercials that got Connors started in his acting career.

"The chemistry of the '56 Angels was such that it didn't really matter who you were with," Speake said. "The camaraderie was there. We moved as a unit. When ball players root for each other and have the talent that was on that team, you're going to have a winner."

Speake returned to the Cubs in '57. Scheffing was the new manager and hopes were high - until the season started.

The Cubs lost 12 of their first 15 games. They didn't win a home game until five weeks into the season. By the second week, they were in last place where they finished tied with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Speake improved on his '55 numbers, batting .232 with 16 home runs and 50 RBIs. One of the homers was a two-run shot in the sixth inning at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field that broke up a no-hitter by the Dodgers' Sandy Koufax.

In 2001, Dwight "Red" Adams, a veteran Coast League pitcher, was reading a list of his '56 Angels teammates. "Gentleman Bob," he said on seeing Speake's name. "He was a gentleman - a quiet guy who could go any place in the world and get along with anybody. He could've been a preacher, a lawyer, or any damn thing he wanted to be."

In 1965, five years after leaving baseball, Speake and several business colleagues started American Investors Life Insurance in Topeka. The company merged with Amerus in 1997 and then was acquired by Aviva Life in 2006. A decade later, the company was worth $400 billion.

Speake could only imagine such lofty numbers with the Cubs in '57. The best he could do was his .375 batting average as a pinch hitter - second best in the league.

That got the attention of the Giants and their manager, Bill Rigney.

Speake was a Giant-killer in '57, getting 17 hits in 58 at bats, including three homers and a triple, for a .293 average.

So, the following spring the Giants acquired Speake in a trade for outfielder Bobby Thomson. The Cubs and Giants were playing in Mesa, Arizona, the next day. "We walked across the field and traded uniforms. I became a Giant; he became a Cub."

Rigney explained the trade to Speake: "Bob, let me tell you why we want you. You're killing us as a pinch hitter. We want you to kill the other guys. We've got this kid coming up, but we don't think he's going to make it. So, we want you to play first base."

"Who is this kid?" Speake inquired.

"Orlando Cepeda," Rigney replied.

"I played against him in winter baseball," Speake said. "He's just a kid but I'm telling you, he's going to be something."

Cepeda proved Speake right, winning National League Rookie of the Year honors as a 20-year-old and going on to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

"The Giants put me on waivers twice in 1958," Speake said. "And the Cubs claimed me twice. So, the Giants pulled me back both times. They never put me up again."

Speake was primarily a pinch hitter for the Giants. The numbers caught up with him. In 52 plate appearances, he managed seven hits and eleven walks. Overall, he batted .211 with three home runs.

The '59 season was more of the same. "I'm 28 years old and I'm sitting there wondering when I'm going to get to play. First base? Not a fat chance. Willie Mays was in center so that's taken care of. Their farm system had blossomed. They had Leon Wagner, Willie Kirkland and Felipe Alou in the outfield - all good, young players."

Speake was sent to Phoenix, the Giants' farm club in the revamped Coast League. He hit 20 home runs in 101 games and got a glimpse of another future Hall of Famer - first baseman Willie McCovey. By the end of the season, McCovey was playing for the Giants and ravaging the league with a .354 batting average. Cepeda was now in left field, the other position Speake played. "The writing on the wall was there for me as far as the big leagues and playing every day."

Speake returned home to Springfield and teamed with friends to open a 16-lane bowling establishment. "I told the group if you want to talk baseball, I can talk all night. But if you want to talk business, you're going to have to talk slow. And sometimes twice."

He soon realized that a small bowling alley wasn't going to cut it. He tried to incorporate three other bowling houses in Springfield into a multi-recreational operation but that didn't work out.

Speake learned a valuable lesson from bowling that helped him succeed in the insurance business. "If you're going to sell something, whether it's a product or service, you must create a relationship. That's true in the bowling business as well as the insurance business with mom and dad at the kitchen table.

"In the insurance business, it's not only the relationship but it's also service. It was mandatory that our employees recognized that the agents were independent and could act so. Our service had to be supreme. That's the bottom-line to our success."

The team picture of the '56 Angels on Bob's office wall symbolized his success on and off the field.

NOTE: Bob Speake is featured in the book, The Bilko Athletic Club: The Story of the 1956 Angels, that can be purchased for $30 plus $5 shipping by contacting Author Gaylon White through the contact section of this website.

Bob Speake belted 16 homers for the Cubs in 1957, including a two-run blast in the sixth inning that ended a no-hit bid by 21-year-old Sandy Koufax, a future Hall of Famer. Listen to Jerry Doggett, a Brooklyn Dodgers announcer, call the shot.

The 1956 Los Angeles Angels, also known as "The Bilko Athletic Club," are arguably the last great minor

league team before the majors expanded in 1961, diluting the talent in the minors. The Angels won 107

games, posting a .297 team batting average and belting 202 home runs.

(Courtesy Dave Hillman)

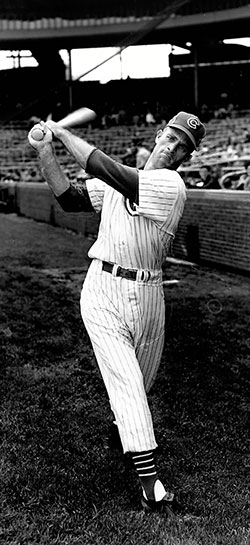

2. Bob Speake described the '56 Angels "waffle-weave" striped attire as a "winner's uniform - you had

to be a winner to wear it to keep people from laughing at you."

(Author's collection)

Bob Speake spread mayhem throughout the National League in May 1955, blasting 10 homers as a

rookie for the Chicago Cubs to earn the monicker "Wonder Boy of the Ozarks."

(Author's collection)

In four seasons with the Cubs and San Francisco Giants, Bob Speake batted .223 with 31 homers

and RBI's. He played for the Los Angeles Angels in 1956, hitting .300 with 25 dingers and 111

RBI's.

(Author's collection)

Batting behind Steve Bilko, this was a familiar sight for Bob Speake, No. 27. Bilko poked

55 homers for the '56 Angels.

(Author's collection)

L-R, '56 Angels teammates Dave Hillman, Gale Wade and Bob Speake had their own reunion in

October 2002 at Hardee's in Newland, North Carolina. "As the old saying goes, we've just got

to sit back now and smell the roses," said Hillman, a 21-game winner for the team. "See the

grass that's on the other side and talk about what we've done." Wade played centerfield, hitting

.292 with 20 homers and 16 stolen bases.

(Photo by Gaylon White)

Dave Hillman, far left, and Bob Speake, far right, displayed their PCL championship rings while

Gale Wade looked on at their 2002 meeting in Newland, North Carolina. "That particular year all

seems like a dream to me," Hillman said of the '56 Angels who won 107 games and finished 16

games ahead of the second-place Seattle Rainiers. "Everybody was focused. They knew what they

were going to do, what they had to do, and they went out and did it. And they did it as a team.

It's a dream to me. It was a dream team."

(Photo by Gaylon White)

Joe Stanka, far left, eavesdropped on the bantering between Bob Speake, center, and Gale Wade

at the 2006 Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri (KOM) League reunion in Carthage, Missouri. Stanka grew

up in Oklahoma and pitched for the Angels and Sacramento Solons in the PCL before moving up to

the majors with the Chicago White Sox in 1959. The trio played in the Class D KOM League, Speake

and Wade becoming life-long friends after roaming the outfield together with the Cubs and Angels.

"If he had to go through a wall to win a ballgame, he'd go," Bob said of Gale. "He had so many

knots on his head, he had to shave the hair off. I always credited him with running me into the

wall in St. Louis. He never denied it."

(Photo by Gaylon White)

This wood statuette of Bob Speake was made and marketed by Jim Fanning, a catcher for the

'56 Angels who went on to become a manager and front office executive for the Montreal Expos.

(Photo by Gaylon White)

©2024 GaylonWhite.com